|

|

|

Some Thoughts on Melee Fighting in the SCA

By: Jester of Anglesey

Introduction

The SCA was created by people who wanted to recreate the chivalric ideals of the High Middle Ages and embraced by people who wanted to club each other with sticks. For the former we have the pagentry and spectacle of the tournament, for the latter the mud and confusion of the battlefield. I'm a hit'em-with-sticks person myself and when circumstances prevented me from active participation in the SCA for several years I set out to learn about becoming a better melee fighter. What I discovered was, at first, disheartening. There simply wasn't much information out there for the SCA melee fighter. The secrets of melee fighting, like those of individual fighting, were/are locked in the heads of experienced heavy fighters throughout the known world. It was actually easier to locate good quality treatises on single combat than it is to find treatises of any sort on melee combat. (1)

After I had thought about this a great deal, and done a lot of searching and reading in the meanwhile, I came to understand the reasons why this is so. To begin with, single combat is simpler than a melee. There is no need to communicate your intent to ten different minds, no need to coordinate your actions, no need to have a picture of what's going on more than twenty feet away, and in general fewer options of all sorts. I am not downplaying the skills required to be a good heavy fighter, just trying to point out that single combat is generally less complicated than melee combat. You are, of course, welcome to disagree. Furthermore, many experienced melee fighters do not publish their thoughts and experiences. Some are not interested in this, some feel that they have little to contribute, and others are interested in protecting their arcane and hard-won knowledge. What discourses on SCA melee combat exist are generally of a like nature. The author is introduced, the publication of the piece is justified, the nature of the problem is stated, and solutions are provided in the form of organizational and tactical suggestions organized, more or less, according the views of the author.

I am not qualified to write this article. While this seems, on the face of it, to be an absurd statement to write on the first page of a 30+ page work it is still my honest opinion. I've read a great deal, I've observed and theorized, but I've never led large groups in SCA melees. In fact, my friends have a saying "Don't let Jester make the plan" based on my performances leading small groups. Let there be no doubt as to my lack of qualifications and my complete awareness of this fact. Nor am I a good single combat fighter. I have never made the time to approach SCA fighting with the proper attitude and commitment so I'm as bad now as I was when I started in 1991. This article represents very little original thought on my part, however. 99% of the information contained in this paper has been drawn from a wide range of sources: books, articles, newsgroups, personal conversations, classes, etc…

The organization of the article and the intellectual distinctions that I make are largely based on the doctrines of the United States Army. The opinions I express regarding how melee fighting should be conducted in the SCA are largely based on the doctrines of Anglesey. This is the background I am coming from and, though I constantly strive to be objective, it colors my perceptions. I would like to express my thanks to Baltazar of Anglesey. Baltazar is the person most responsible for introducing me to the SCA and teaching me the joys of melee fighting. The ideas that lead to the research which resulted in this article were given to me by him. Thanks, Bzar.

What I hope to do in this article is provide a starting point for

future discussions on this subject. I will put forth my opinions, theories,

and conceptual organization for all who care to comment and critique. I

hope that genuine knowledge will acrete around this article in much the

same manner that an oyster creates pearls.

Organization

Principles

In the course of my readings on ancient and medieval military history I came to believe that SCA combat can be divided into three levels which closely mirror certain time periods and systems. The first level is single combat. The single combat closely resembles the jousts and tournaments of the High Middle Ages in Western Europe. (2) Single combat is exemplified by Crown Tournaments and the events hosted by the various tournament companies. The second level is small group combat. Small group combats are the melees that take place at countless fighter practices and small tourneys throughout the world. They closely resemble primitive tribal combat from any time and place. The third level is the large group combat. Large group combat takes place only at large events such as Pennsic, Gulf Wars, Estrella, and Lillies. It is fairly rare and closely resembles the battles that took place in Greece prior to the Peleponesian Wars. There are no clearly defined gradients that separate these levels. They exist on a sliding scale where one level transitions gradually into the next.

SCA large group combat (hereafter referred to as 'melees') is an artificial construct. We adhere to rules which compromise the realism of the simulation for the purposes of making it reasonably safe. So, from the very beginning we deviate from reality and there is no going back. This means that while we may attempt to recreate Medieval history, we can never truly achieve this goal in all aspects at all times. Some truths, however, remain unaffected by our deviations.

The most fundamental of these truths is that logistics drives organization. Simply put, you can only create and sustain an army that you can supply. Depending on the time and place and level of development of the art and science of warfare there are various functions that can be lumped together under the broad heading of logistics. The four most common functions are: Supply, Transport, Maintenance, and Services. The ability of a state or organization to meet the needs that these functions represent largely determines the type of military organization they can create and sustain.

The fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of the feudal states provides an excellent example of this. Consider the Roman military system after the time of Marius. The army was composed of professional soldiers, primarily infantry, who lived and trained in large groups. This was made possible by an economic and political infrastructure capable of marshalling the resources needed to support such an organization (3). Contrast this with the feudal military system that came after the fall of Rome. Medieval monarchs were not ignorant, they knew of the Roman military system (which continued in various forms in Constantinople) but they were unable or unwilling (due to political concerns, how many Barracks Emperors were there?) to support large, standing armies of infantry (4).

To determine what form of organization you wish to use, you must

first look at all the factors which affect your ability to create the army

or unit you want. Frankly, attempting to list all of these factors would

be boring and largely unproductive since the factors can vary from place

to place and time to time. Of the four general factors (supply, transportation,

maintenance, and services) the first three are summarily dumped on the

individual participant. The fourth, services, is largely a function that

is filled on an as-needed basis by volunteers. The one aspect of services

that I am concerned with is training.

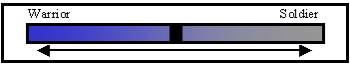

| Because this is a game (a point I will reiterate ad naseum throughout this article) we tend to more closely resemble the medieval model than the Roman model of organization and training. This model is based on the patron-client model that prevailed among the Germanic tribes that superceded Rome. (5). Military training models can be thought to exist on a sliding scale. At one extreme lies the warrior model of organization, at the the other the soldier model. The warrior model emphasizes individual training while the soldier method emphasizes group training. Most organizations tend to fall somewhere between the two extremes. In the SCA the typical organization tends to favor the warrior method. There are many good reasons for this. The creation of effective large units requires a substantial logistical commitment. In modern terms we would have to require a commitment of time and effort that many people are unable or unwilling to make. It is much easier to create a set of standard commands and educate individuals. In this way the lone fighter in the Canton of Middle of Nowhere can integrate himself into any unit formed from the fighters of his Kingdom. |  |

Because this is a game, and most of us have busy lives outside our hobby, there is a strong tendency to reduce the amount of work to the absolute minimum. For this reason, foremost among many others, the SCA tends to favor a warrior system organization. I do not. I favor a soldier system organization because I feel that a tight unit will react better than a group of individuals when the plan goes bad, and the plan always goes bad. I believe that my system does not replace the warrior system organization, rather it refines and supplements it by going one step further.

A unit based system does not come without its own set of drawbacks.

It can be more difficult to integrate groups of small units into a single

large unit than it is to integrate the same number of individuals into

that large unit. This is because the small groups inevitably develop their

own techniques, lingo, and customs. This complicates communication and

command and makes it more difficult to achieve a uniform weapons distribution

in the unit because the commander usually ends up breaking up the small

groups. It is exactly because of those same traits that I believe units

are more effective than groups of individuals. I believe that an army composed

of 3 to 8 man (or larger) groups will perform better than an army composed

of individuals for reasons that I will outline below.

| "War is teamwork. It requires learning and can be practiced efficiently only after intensive training, usually accompanied by firm, sometimes savage, discipline." (6) |

Obviously none of the sane people in the SCA are going to voluntarily

undergo 'savage discipline' for the sake of a more realistic recreation

or to satisfy my personal opinion of how melee units should be organized,

but this does highlight the key aspect that separates individual combat

from large group melees: organization. Observe any melee and note that

the successful teams fall into three categories: 1) better organized 2)

better fighters and/or 3) numerically superior. The third category is a

simple expression of the attrition equation (see The

Blue Company Melee Manual). The second category covers 'ringer-teams'

composed of highly skilled individual fighters. In a small to mid-sized

melee they can often prevail by turning the melee into a collection of

one on one battles. Even in large melees, when facing organized fighting

teams, they tend to die hard by virtue of their skill and experience. The

first category covers organized fighting teams.

| "Four brave men who do not know each other will dare not attack a lion. Four less brave, but knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of mutual aid, will attack resolutely. There is the science of the organization of armies in a nutshell." (7) | |

| "When a soldier is unknown to the men who are around him he has relatively little reason to fear losing the one thing he is likely to value more highly than his life - his reputation as a man among other men." (8) | |

| "... Put men from the same villages together and the sections of ten and the squads of five will mutually protect one another." (9) |

These three quotes reach to the root of organizing fighting teams. Men who fight individually do so for their own reasons and this paper has no desire to explore those reasons. Men who fight well as members of a group do so, in part, because they value the opinion their peers hold of them. There are some problems with this generalization, remember the individual motivators, but as a rule of thumb it holds true. Certain other principles are evident in these quotes. "…knowing each other well…" "…unknown to the men who are around him…" Du Picq, Marshall and Wu are referring to the bonds between men. Close association, shared experience, and time are the only ways to form these bonds. "…sure of their reliability…" Trust is an essential element in any successful relationship. If close association, shared experience, and time reveal to one warrior that another is untrustworthy, then the bond between those men will be weak at best. One will not respect the other and the positive performance motivator is diminished or lost.

Let us consider some historical examples that support this assertion and reveal other principles. We will begin with the Greek military during the Fourth Century, B.C. We will then move on to the example of the Roman army. Finally we will jump ahead to the Swiss Cantons and their pike squares.

There are many studies of Greek Warfare with a great deal of merit, but for factual content and reader accessibility, The Western Way of War by Victor Davis-Hanson is hands down my favorite. In it, Mr. Davis-Hanson discusses the conditions of warfare in ancient Greece, from the preparation to the aftermath. Because the physical conditions in Greece made the supply of armies in the field difficult warfare tended to be comprised of short periods of armed conflict followed by truces that allowed each side to re-arm. Because terrain conveyed such an advantage to the defender, the attacker would refuse battle. The defender, in turn, could not take advantage of their position because they lacked the supplies to maintain it. So battles tended to be fairly evenly matched affairs that took place on relatively level terrain between armies which were similarly equipped and of similar capabilities.

Greek armies were made up of free citizens whose status in civilian life was partly tied to the quality of arms they could provide for themselves in time of war. The wealthy formed the heavy infantry (hoplites) and cavalry (cataphracti) while the poor supplied the light infantry and missile troops (peltasts). Within these branches they were organized by family, clan, and tribe. The performance of each man would be scrutinized and remembered by the people who formed his entire social world. This was a powerful incentive to perform well or, at the very least, not to perform poorly. Further incentive was provided by the personal relationship of each man with the men around him. Though we have no monopoly on dysfunctional families in our age we have to assume that most men cared about the welfare of their relatives to some degree. They would have been motivated to fight well lest their failure doomed their friends and family.

The battle would begin with the armies forming up within sight of each other, but out of range of a quick charge. The peltasts would form in front of the hoplites and on the wings. The cavalry would station themselves on the wings. The hoplites would form up in the center. Mass was the key to the hoplite charge, so generals were reluctant to have less than six ranks and more commonly eight to ten. Another reason for the many ranks was to allow the most experienced men to be in the front, the younger men in the middle, and the oldest men in the rear. There was likely no reserve as the General commanding the army would be down in the front line and in no position to direct them. The battle would begin with skirmishing between the peltasts and cavalry as the hoplites slowly advanced to within charging range. Once this range was reached the peltasts would withdraw from the front of the hoplites to the wings. The hoplites on either side would sing a song, a paen, and then charge. The initial collision must have been fearful as the men in front were pushed through a wall of opposing spearpoints by the mass of the men behind them. We know that spears were broken in this initial charge and the men in front became involved in a pushing contest while the men behind them added their weight to the press, thrust at the enemy with spears, or stabbed fallen foes with butt-spikes as the phalanx advanced. The old men in the rear would act as a stabilizing force, preventing the young men from panicking and fleeing, if necessary by force. In the front pockets would form and allow men to bring their swords into play or to be cut off from their comrades and killed by the enemy. Eventually, one side would lose the will to fight. Perhaps the peltasts and cavalry appeared in the rear or a popular commander was believed to have been slain. Whatever the cause the rout would begin with troops in the rear taking flight and once it began it was almost impossible to stop. Curiously, the actual casualties up to that point would have likely been relatively light (9). The bulk of the casualties occurred during the pursuit of the routed side.

Once routed the soldiers of the defeated army had one thought in mind: survive. Armor, reputation, wealth, all might be restored in time, but only if the soldier survived. The victorious hoplites would pursue the defeated hoplites as they desperately sought to break contact. To break contact they would abandon weapons, armor, and shields to lend speed to their flight. Unfortunately this would make them vulnerable to the peltasts and cavalry who continued the pursuit once the hoplites broke off. If they were fortunate enough to evade the peltasts and cavalry, the defeated soldiers stood a good chance of getting home. Once home they could rearm themselves to face battle another day.

The Romans were well aware of the manner in which self image helped

soldiers to stand firm against the foe. In his Epitoma Rei Militaris

(or

De Re Militari) Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus offers us the following

quotes:

| "For the youth in whose hands is to be placed the defence of provinces, the fortune of battles, ought to be of outstanding breeding if numbers suffice, and morals. Decent birth makes a suitable soldier, while a sense of shame prevents flight and makes him a victor." | |

| "It was a divinely inspired institution of the ancients to deposit 'with the standards' half the donative which the soldiers received, and to save it there for each soldier , so it could not be spent by the troops on extravagance or the acquisition of vain things…..Secondly, the soldier who knows that his spending money is deposited 'with the standards' never thinks of deserting, has greater love for the standards, and fights for them more bravely in battle, since it is human nature to care most about things on which one's living depends." |

Not satisfied with the sense of shame, the Romans made sure to include the financial factor. Those troops who lacked a sense of shame, after all, were all the more likely to have a sense of greed. This was necessary since by the time Vegetius was writing the Roman army was largely composed of barbarians, either inducted into the legions individually or wholesale as members of the foederati.

Whether the Romans recognized it or not, they also took advantage of other bonding measures, most notably the shared experience. Roman recruits all went through the same rigorous training process. The value of this shared experience was almost as great as the training itself, for the hardships they endured together brought them closer together and gave them an experience in common with the rest of the army. The stigma of the army, the tattoo they received upon passing the entrance examinations, was more than a means of identifying deserters, it was another bond shared by the soldiers.

The Romans also recognized the value of success in building morale. Vegetius recommends sending raw troops out with experienced troops to face a small number of foes. The experience, he contends, gave them a sense of accomplishment and had the added value of making warfare familiar. The next time the troops faced a battle they would do so with the knowledge that it was possible to survive a battle, the expectation that they would win, and less fear of the unknown.

In examining the Swiss we find ourselves returning to the Greeks. The number of similarities is astounding. Both groups lived in mountainous terrain that forced them to live in small, self-governing communities. The agricultural conditions were such that it was difficult to support a specialized warrior group or full-time army. This in turn meant that each free man was obligated to defend the community and that an army could not stay in the field for long. Both nations were faced with the presence of a powerful Empire close by them; the Greeks the Persians, the Swiss the Holy Roman Empire.

It should not be surprising, then, that the Swiss created a system much like the Greeks. Unable to have a national standing army, the Swiss created a militia organized along regional lines. Like the Greeks the Swiss were organized by associations, in this case family, village, and canton. Unable to afford cavalry or the heavy armor necessary for close combat, the Swiss adopted the pike. Pikes were well suited for the Swiss organization. It allowed a mass of men to bring enormous power to bear on their foes while those foes were still too distant to respond. The point would impale a horse or rider and the axe would cut through the heavy armor of their noble foes.

Where the Swiss deviated from the Greek model was in their superior articulation. Though in theory the Greeks had multiple maneuver units organized by tribe or by city-state, in practice the heavy infantry formed a single massive unit which could only execute an advance with any degree of control. The Swiss organized their towns or cantons into squares which could maneuver independently of each other. Their ability to defend themselves from any direction freed them, in theory if not always in practice, from the need to maintain strict battle lines and to anchor or defend their flanks. Such a system was only possible with well trained and well disciplined units that were, above all, cohesive.

The Swiss ensured cohesion through their organization, rigid discipline, and their actions. Military service was taken seriously. Failure to report for duty was punishable by death. Fleeing in the face of the enemy was punishable by death. Stopping to loot was punishable by death. Numerous other offenses were punishable by, of course, death. This discipline undoubtedly contributed to the cohesion of the Swiss forces. But it was their isolation from the rest of society that most contributed to their sense of identity. This isolation was the result of actions on the part of the Swiss which transgressed the accepted norms of the societies they were in conflict with.

The Swiss were brutal fighters who rarely took prisoners. When they did take prisoners they generally ignored the conventions of the time and slaughtered them. There were sound reasons for this. The Swiss were outnumbered by militarily powerful foes who could conceivably muster a sufficiently large force and conquer them. The Swiss had to strike terror in the hearts of their foes. Men who faced the Swiss knew there would be no quarter given if they lost. At the time, the practice of ransoming prisoners was widespread and soldiers were apt to grab a prisoner and then leave the battlefield, with prisoner in tow, as quickly as possible. Moreover, the Swiss had to fight aggressively in both the tactical and strategic sense. They couldn't keep an army in the field for long, they needed a clear resolution, quickly. In a tactical sense the Swiss were also forced to be aggressive. Their funds went to procuring weapons, not armor. In order to win a battle the Swiss had to kill their foes through offensive action. They had to strike blows, and do it before the enemy could close with them and bring their weapons to bear.

The actions of the Swiss made them international pariahs. They knew that capture was the same as death, in some cases worse since it might mean a slow death. Victory was their only option. The Swiss, in any case believed that they would win. Convinced of their invincibility they would often attack against horrendous odds. Strangely enough, they sometimes won. But even when they didn't they inflicted severe casualties upon their foes and generally fought to the last man.

The organization of fighting teams can be reduced to four general

principles:

| 1) Use positive peer pressure and take advantage of the human social instinct. | ||

|

||

| 2) Create a sense of group identity. | ||

|

||

| 3) Create an aura of success. | ||

|

||

| 4) Maintain rigid discipline. | ||

|

Specifics

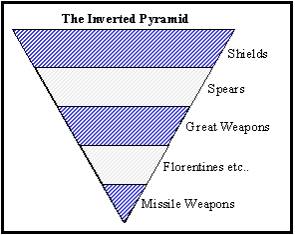

| When creating organized fighting teams most manuals focus on the ratios of weapon styles. They specify so many shields for each spear, so many spears for each pole, and so on down the line. In general these ratios all take on the form of an inverted pyramid, shields at the top, then spears, polearms and great weapons, the odd weapon styles, and archers and other missile troops at the bottom. This inverted pyramid carries over into tactical organization where it manifests itself in the 'two up, one back' formation that occurs down at the most basic team level and on up to the entire army. The problem of creating maneuver units can be expressed in two words: articulation and mass. Mass is what the Greek phalanx had. Mass is what enabled heavy cavalry to break up infantry units and rout them. It is the momentum of sheer power. Articulation is what enabled the Romans to defeat the Greeks. They couldn't break a phalanx by attacking it frontally, so they used part of their force to flank them and attack them from the rear. The smaller Roman units could be maneuvered separately and take advantage of the opportunities this created. |  |

The desire for mass and maneuverability has been a dilemma of army organizers for centuries. The more you have of one, the less you tend to have of the other. Organizers have dealt with this problem by creating small units that can be combined into larger units. The Romans had maniples, cohorts, centuries, and legions. The condottieri had lancie, poste, bandiere, and compagnie, among many other names. Modern armies have teams, squads, platoons, companies, battalions, regiments, brigades, divisions, and armies. The term most frequently used throughout the Middle Ages was the lance. Instead of the teams, triads, or units some manuals propose I will stick with the lance for reasons of verisimilitude, flavor, and simplicity.

The lance was organized around the mounted knight. This was done primarily for logistical reasons. The wide dispersion of forces under what was essentially a militia system meant that it was difficult to bring together large concentrations of weapons types on a regular basis. A village or region might produce two archers, three men-at-arms, a few squires, and the knight who administered the region. These men would serve together and, more importantly, be supplied together. Since each region served under terms that might be subtly different they had to be administered by region. Of course this also meant the men were serving with their friends and family which contributed to their cohesiveness. Once we leave the purview of the militia forces and move into the area of paid professionals we find a more systematic organization of the lance but one which was still organized around the nucleus of the heavily armored, mounted warrior.

The SCA relies predominantly on a warrior system based on regions. This is particularly true in low population density kingdoms and less true in high population density kingdoms, where independent households, mercenary groups, and other organized units become possible. The lance, therefore, will be comprised of the fighters who typically make up the local fighter practice under the leadership of one of their number.

This makes it impossible to set an exact size for a lance. Each region will contribute according to their means, not according to some artificial standard. I personally favor a unit size of five to eight fighters. Beyond this upper limit it becomes difficult to maintain control of the unit without subordinate leaders. If a region has more than this number then they should form more than one lance and select an experienced fighter to direct the lances. It is important that commanders not break units up if that can be avoided. An exact weapons mix is less useful than a cohesive unit.

I believe that this system provides for greater cohesion and allows for better and more realistic training prior to large battles. It is not perfect, though. The fixed composition teams proposed by several authors have the advantage, when properly implemented, of making fighters think in terms of weapons mixes. If a team suffers attrition it can hope for an individual fighter who recognizes the need to balance the weapons mix to step in. But of course that new member probably has not worked with the team before and the fundamental advantage of a team, coordinated action, is degraded or lost.

While the exact size of a lance cannot be set, there are other actions that can be taken to create a cohesive team. Distinctive attire is, perhaps, the most important. A well practiced and highly skilled team whose members cannot be differentiated from the other schmoes around them will not be effectively utilized. Commanders will attempt to break them up to fill in the gaps in other units and be frustrated when the team members resist. A lance should have tabards which clearly identify them. If a region has more than one lance then those lances should share certain characteristics, generally a color scheme. Lances should always practice as such. The practice of breaking up units to 'make the sides even' should generally be avoided. The region should make efforts to recognize the efforts of their lances and the individuals who compose them. If your lance is new, consider a fighter practice raid. On a specified date, gather the lance and head off to a fighter practice you don't usually attend. Armor your people up and publicly challenge the local fighters to best three out of five melees. If you have trained well and scouted the opposition beforehand, then you should crush them handily. After the melees are over, break down the unit to fight individually and then have a couple of friendship melees at the end with mixed teams. Your lance will now have a winning experience to build upon. Repeat this process several times, each time setting your sights a little higher. Not only will this benefit your lance, the fighters of other regions will take steps to ensure that no one comes into their practice and trounces them again. The whole kingdom benefits.

Types of Melees

Within the regulations of SCA heavy combat there are two types of battles: static front and fluid front. Actions in these types of battles can be further sub-divided into offensive and defensive actions. This is a somewhat artificial division for, in truth, there should be no difference between your offense and defense. Both should be carried out aggressively and ruthlessly with the intent of defeating your foe. A well practiced unit can shift from the defense to the offense and back as often as necessary without the need for verbal commands.

A static front battle is typically one in which terrain allows a commander to secure both of his flanks by using the natural geography of the battlefield. These features must absolutely prevent the foe from traversing the feature and physically engaging your forces in the flank or rear. These features may not prevent the foe from engaging your forces if your forces approach close enough. A river, for example, will not stop your foes from engaging you with missile weapons or spears as you cross a bridge or ford. Static front battles limit the ability of a commander to maneuver and to utilize the articulation of his forces. Mass, therefore, assumes a proportionally greater role in securing victory in these circumstances. The restrictions on maneuver also reduce the number of possible actions and counteractions that may be taken. But this also allows a commander greater scope to utilize pre-planned maneuvers and strategems secure in the knowledge that his forces only have to face a foe in their forward arc. Loss of options translates into more control for the commander and less need for decentralization of command.

A fluid front battle is typically one in which the terrain does

not provide the commander with barriers to movement with which to secure

his flanks. The foe is free to exploit openings in the line or to maneuver

around and bypass the line altogether. No SCA battle is a true fluid front

situation. We are constrained by the pre-determined limits of the designated

battlefield and cannot transgress those boundaries. A fluid front situation

only occurs when a commander lacks sufficient troops to form a battle line

from one boundary to its opposite boundary. In a fluid front battle the

ability to bring mass to bear is limited by the ability of the opposing

forces to simply move out of the way. Maneuver, therefore, assumes a proportionally

greater role in securing victory in these circumstances. The wide range

of possibilities for maneuver also reduces the ability of the overall commander

to execute pre-planned actions, which assume the existence of circumstances

the foe may not provide, and to personally direct the actions of his troops.

The increase in the range of options translates into less control for the

commander and the need for decentralization of command. In these circumstances

it is vitally important that every potential commander, i.e. everybody,

be aware of the assigned mission of their unit and the role they play in

the commander's overall vision of how the foe will be defeated.

Individual Roles

There are six varieties of fighters who are allowed to participate in heavy combat. All fighters fit into these six categories. The first category is shieldmen. This category encompasses all fighters who use a shield and any other sort of weapon; mace, hammer, sword, etc… The second category is spearmen. This category encompasses all spear fighters, from 6 foot to 9 foot, except for those who use shields. Generally speaking there are no fighters who use a 6-9 foot spear and a shield because of the problem of controlling the spear with one hand. Fighters who use a shield and spear fall into the fourth category. The third category is great weapons. This category encompasses the large slashing weapons; greatswords, pole-arms, etc… The fourth category is florentines. This category encompasses the two weapon fighters; two swords, sword and dagger, sword and madu, weapon and buckler, etc… I do not include buckler fighters in the first category because they rely heavily on movement to augment their defense and are generally not capable of mounting a static defense. The fifth category is heavy missile troops. This category encompasses every fighter who uses a projectile weapon and wears heavy-combat legal armor. The sixth category is light missile troops. This category encompasses every fighter who uses a projectile weapon but does not wear heavy-combat legal armor. I personally feel that light missile troops should not be allowed to participate in heavy combat for reasons of safety and equity, but many kingdoms currently allow them, so we must discuss them.

Each category of fighter has specific roles to play in each type

of fighting scenario. These roles are guidelines, not rules, and it is

the responsibility of each fighter to learn when to move from one role

to the next. Experience is, ultimately, the only guide.

The role of first category troops in general.

Shields are the foundation of every unit which will physically

engage the enemy. A commander who has shields and no other troop types

can still successfully engage the foe. The area in which a shield fighter

can directly engage the foe is a 5-6 foot radius circle drawn from the

center mass of the fighter. This circle can be extended 2-3 feet with the

use of a forward step which widens the stance. A fighter can influence

the actions of opponents within a 6-10 foot radius circle based on the

ability of the fighter to quickly advance a full stride and strike. This

sphere of influence varies not with the ability of the shieldman, but with

his foes' perception of his ability. The primary job of a shieldman is

to maintain the integrity of the unit by preventing the foe from penetrating

their line and disrupting the unit. This is primarily a defensive action

and can involve a great deal of standing around and staying alive without

much opportunity to hit anyone. In this sort of a situation it is useful

to have a large shield. Large shields are difficult to maneuver on broken

fields or in wooded terrain, but this is a measure of skill on the part

of the individual shieldman. Where a large shield truly becomes a hindrance

is in a chaotic situation where the ability to move quickly is at a premium.

These situations rarely occur in SCA combat because we do not allow our

participants to strike from behind. Because of this a large shield, be

it a kite, round, heater, or scutum, is preferable to a small shield 9

times out of 10.

The roles of first category troops in a static front situation while on the offense.

The exact role a shieldman must play will depend on a wide variety

of factors. In a static front situation the primary role of the shieldmen

is to maintain the line. This does not involve killing anyone. That task

typically falls to the second and third category troops. Shields should

advance in unison while continuing to defend the troops behind them. If

a shieldman wants to be effective on the static front offense then he should

use a weapon with a stabbing tip. The mast majority of the slashing blows

a shieldman uses require movement to set them up whereas the thrusting

tip can be used with an minimum of movement. The thrusting tip of a fairly

short sword can find holes that a cutting blow cannot. On the other hand,

it is much more likely that a cutting blow will be aknowledged in the press

where any but the hardest thrusts might be discounted as jostling. When

it is time for the shieldmen to engage they must be disciplined and aggressive.

Discipline maintains the line, aggression kills foes. Close action of the

type dictated by a charge or a pulse should place a premium on defending

by aggressively attacking. If the attacking line is throwing more blows

than the defenders, then the defenders will spend more time defending themselves

and less time throwing blows. Granted this is circular logic, but the idea

is basically sound. However, at no time during this aggressive defense

should the shieldman forget that his primary mission is to protect the

second and third category troops behind him by staying alive and maintaining

the line.

The roles of first category troops in a static front situation while on the defense.

The shieldman contributes to the overall accomplishment of the mission principally by staying alive and functioning as a human barrier. Should the opportunity arise the shieldman should not ignore the chance to make a clean kill, but he should ignore anything less than a sure thing. This is not to say that the shieldman should not swing his sword. The shieldman can help keep the foe at a respectful distance simply by throwing that sword out at a target every few minutes. The key, when doing this, is to make sure the arm that carries that sword out comes back to the protection of the line in one piece.

The time when shieldmen are most valuable is when the foe charges.

In these instances it is up to the shieldmen to stop the physical advance

of the foe. The second and third category troops will do the actual killing

and reserve troops of the first and fourth category will mop up troops

that do break through the line. The front rank shieldmen must not yield

to the temptation and be drawn into a confused slugfest that leaves the

line open to penetration. Close and re-establish the line as quickly as

possible. For more guidance on breaking a charge see Appendix .

The roles of first category troops in a fluid front situation while on the offense.

There are two types of offense in this situation, the advance and

the penetration. The advance is a measured, general forward motion in which

the primary goal of the shieldmen remains the maintenance of the line.

They continue to provide cover for the second and third category troops

who do the lion's share of the killing. An advance can be at a slow pace

or can be a full charge. Whatever speed it is conducted at it aims at pushing

the foe back along the entire length of your line. The penetration is a

charge aimed at breaking through the entire enemy formation. The primary

troops in this action are the first category troops. But, once again, they

are not trying to kill people. They are trying to disrupt the opposing

formation by pushing through it. They do this by brute force. They do not

stop to kill people. They do, however, push those people to one side or

run over them. A shieldman should be alive when he reaches the far side

of the enemy formation and continues on through. Too many penetration charges

come to a chaotic stop as the first rank, or second and third ranks, stop

to kill foes. This holds up the advance of the ranks behind them and kills

the momentum of the entire charge.

The roles of first category troops in a fluid front situation while on the defense.

There are no defensive situations in a fluid front melee. There

are times when you are temporarily unable to pursue your offensive strategy.

These are times when you have lost the initiative. You must retake the

initiative and begin to conduct offensive actions. The end result of attempting

to defend in a fluid front situation is encirclement and destruction. The

nature of SCA combat creates an exception to this rule. It is possible

to anchor a flank against the field boundary and hold a line. If it is

possible to anchor both flanks and to hold a line across the entire field

then you are in a static front situation, not a fluid front. Any holding

action on your anchored flank will be temporary at best. By definition

the foe will be able to find an opening and bypass your blocking force.

If you are forced to fight defensively in this situation, keep the line

tight, stay alive, break out if you can, and die hard if you can't. A good

commander on the flank will attempt to push the foe against the boundary.

This will inhibit their ability to move and use the foe's mass against

them. By dropping a few of the front rank you create a living wall composed

of foes. This wall restricts the ability of the foe to make a concerted

attack and is a truly elegant way to defend a flank.

| The role of second category troops in general.

"Spearmen are the teeth of a unit." (10) The primary responsibility of second category troops is killing the foe. Remember the example of the Swiss pikemen? A spear is an excellent offensive weapon and a poor defensive weapon; spearmen must attack. In particular, spears must work in conjunction with each other and the first category troops in order to be effective. The goal is for all the spears to kill all of the foe, not for every spearman to kill a large number of foes. A spearman who does nothing but assist other spearmen in killing foes is just as valuable as the spearmen who do the actual killing. Spears should be of the maximum allowable length and should have a sturdy protrusion for hooking shields. Shieldmen should talk to each other and work in ad- hoc teams. One man hooks a shield, another takes advantage of the opening to get the kill. It is very difficult to kill a foe from within his tunnel arc. The tunnel arc is an arc of approximately 15 degrees to either side of the foe which represents the area the foe is concentrating on. This tunnel vision gives the foe an extremely focused view of the threats immediately before him. The spearman must attack from outside this tunnel arc in order to maximize his chances of a successful kill. This is known as attacking on the oblique.(11) The downside to fighting on the oblique is the loss of range this entails. The maximum range of a spear is about 9 feet plus the length of the spearman's arm, approximately 2 feet more (12). This 11 foot engagement range is decreased when the spear is thrust at any angle off the perpendicular to the opposing line. Spearmen fighting on the oblique can find themselves easy prey to spearmen fighting straight ahead. To prevent this they should, again, work together. While brushing aside spears intended to strike their comrades will save lives, communication will save more lives still. |

|

The roles of second category troops in a static front situation while on the offense.

Second category troops, for the most part, make up the second rank

in these situations. This allows them to make maximum use of their offensive

range while offering them the protection of the shield wall. In some rare

situations the second category troops will be able to move forward into

the front rank, temporarily. This can only happen in situations where the

foe is prevented from charging. When the line advances the second category

troops allow the third category troops to pass through their line. The

third category troops then become the second rank, and the second category

troops become the third rank. In this way we are able to bring the maximum

numbers of weapons to bear on the foe by using the different weapon ranges.

In many situations the first and third category troops will fill the available

space and the second category troops will not be able to bring their weapons

to bear. During these times the second category troops can still contribute

to the offense by defending the first two ranks from overhead blows. Do

this by forming an umbrella of weapon shafts above the first two ranks,

deflecting, and catching overhead swings from the foe.

The roles of second category troops in a static front situation while on the defense.

Second category troops traditionally make up the second rank. Their

job while the line does not advance is to kill people. Second category

troops actually get to do more killing on the defense than the offense.

The roles of second category troops in a fluid front situation while on the offense.

In fluid front situations second category troops are still in the

second rank but they may find individual members floating into the first

rank from time to time and will almost certainly find that third category

troops are now members of the second rank. Second category troops must

continue to strike offensively. They will do the bulk of the killing from

within the protective base provided by the first category troops.

The roles of second category troops in a fluid front situation while on the defense.

Again, there are only transient moments when you are not attacking

in a fluid front situation. Second category troops should continue to strike

aggressively and kill as many of the foe as possible. Once sufficient numbers

have been killed it will be possible to resume the attack.

The roles of third category troops in general.

More so than any other weapons style, the troops of the third category

must be aggressive, ruthless, and fast. Like the second category troops

the strength of third category troops lies in the offense. When they are

called into action third category troops go from a medium range situation

to a close range situation very quickly. In a crowded melee their movement

will be restricted and movement is their primary defense. They must kill

the foe before the foe uses this fact to their advantage. In a sense third

category troops are shock troops. They strike hard and fast, let others

clean up the mess they leave, regroup behind a protective screen of first

and second category troops and then do it all again.

The roles of third category troops in a static front situation while on the offense.

Third category troops traditionally make up the third rank. When

the line advances they must move up and become the second rank. They will

be responsible for doing the bulk of the killing. Their shorter shafts

(in comparison to the second category troops) allow them greater mobility

in attacking the foe and their slashing attacks can rain down from above

with crushing strength. Once the line has stabilized third category troops

must be savvy enough to let the second category troops back up into the

second rank.

The roles of third category troops in a static front situation while on the defense.

Third category troops have even less fun than first category troops

while on the defense. They are taking actions which are mostly defensive,

but from behind two ranks of troops. They don't even get to snarl at the

foe, they generally get to look at the backs of helms for an hour or so.

They also get to deflect overhead attacks and make the occasional foray

into the second rank to replace a downed second category trooper until

a replacement can be found. But when the foe charges, the third category

troops must fling themselves in the fray with aggressive abandon. They

are responsible for killing the foe while the first two ranks physically

contain them. The third category troops must also act to quickly staunch

any breakthroughs. When a charge comes, the third rank assumes the responsibility

for holding the line. The first and second ranks will probably be broken

and the third rank must hold their line, kill the foe, break the charge,

and let the first two ranks be re-established.

The roles of third category troops in a fluid front situation while on the offense.

In this situation the third category troops will find that they

are called upon to join in the formation of the first and second ranks.

Their role is to attack aggressively from within the protective line of

the first category troops. This line is less fixed, however, and third

category troops will often find themselves darting out to take advantage

of opportunities to attack. In this situation the third category troops

should make every effort to enlist the aid of other troop categories to

create opportunities to slay the foe. Third category troops can be usefully

employed on the flanks where they will find greater opportunity to maneuver

and act aggressively.

The roles of third category troops in a fluid front situation while on the defense.

When the front is not attacking, the role of the third category

troops is the same as in a static defensive situation. As soon as the attack

resumes they must again move up from the third rank to the second and first

ranks.

The roles of fourth category troops general.

The strength of fourth category troops lies in the offense and

mobility. Because a large portion of their defensive ability is constituted

by movement, these troops tend to be used as skirmishers and light infantry.

Their mobility and offensive abilities in close makes them invaluable in

broken and wooded terrain. They are frequently used as flanking forces

to turn the foe or deny the flank. They also see a great deal of use as

'mop-up' troops, following behind the first three categories to finish

off the wounded. Finally, they are frequently used as reaction/reserve

forces to be committed against units that break through the line.

The roles of fourth category troops in a static front situation while on the offense.

This is a boring situation for fourth category troops as they must

sit around and wait for the line to make significant advances. During this

time they must be close enough to the front ranks to kill any wounded the

front ranks pass over yet they must remain aware of the need for a constant

flow of first, second, and third category troops through their ranks. If

a breakthrough charge is called for, the fourth category troops will find

themselves dealing with large numbers of foes who have been bypassed by

the front ranks. The fourth category troops must take advantage of the

confused state of these foes to aggressively and ruthlessly finish them

off lest the become a solid nucleus of resistance and collapse the integrity

of the entire formation.

The roles of fourth category troops in a static front situation while on the defense.

Fourth category troops, in conjunction with some first and third

category troops held in the rear, form the ready reserve. When the foe

charges they act to staunch any breakthroughs by hurling themselves upon

the foe in overwhelming numbers. Attack, attack, attack.

The roles of fourth category troops in a fluid front situation while on the offense.

Fourth category troops really enjoy these situations. The float

around the back and flanks and get to do a great deal of fighting. They

reinforce the front ranks when they attack strong points. They mop up wounded

survivors. They harry the foes flanks and herd them into an unorganized

mass to be slaughtered. They plug holes in the line. Fourth category troops

should take care, in these situations, not to separate themselves from

a source of support. The timely intervention of a first, second, or third

category trooper can often mean the difference between success or failure.

The roles of fourth category troops in a fluid front situation while on the defense.

For most other troops this situation is unpleasant, but fourth

category troops generally get to enjoy some good fighting. They prevent

the foe from attacking the flanks of the main body. They act to plug holes

in the line. They staunch breakthroughs. They are in constant motion and

always acting aggressively.

The roles of fifth and sixth category troops in general.

Sir Jon Fitz-Rauf has already written a substantial paper on the

role of missile troops in SCA combat. It is included as an appendix

to this paper and deserves your attention. I will not attempt to make any

new observations and will confine myself to summarizing his key points.

Missile troops are generally used in three roles: individual snipers, small

teams, and massed units. Individual snipers rely on surprise and accuracy

to sneak up on targets and engage them. Small teams work cooperatively

with other troop categories and embody the '20 Yard Pike' concept. By thinking

of them as spearmen with enormous range you can get commanders to effectively

utilize them. Massed units have seen limited use and less success in the

SCA. War conventions that limit the number of arrows an archer may use,

small numbers of available archers and rules that prevent archers from

engaging troops from behind take most of the sting out of massed volleys

of arrows. Fifth category troops have an advantage over sixth category

troops in that they can draw closer to the actual fighting and be more

effective.

Tactics

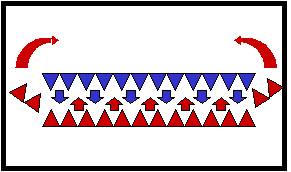

The actual tactics that can be used by a commander are infinite due to variations in terrain, weapons, numbers, etc... But all tactical movements have some basic roots in common. These common movements are illustrated and discussed, briefly, below.

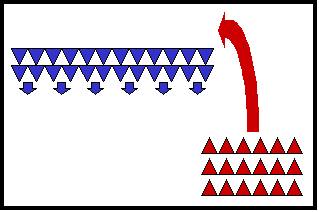

The Frontal Assault

"Hi diddle diddle, straight up the middle." Folk Ryhme.

| The Frontal Assault |

|

| Push Back |

|

| Breakthrough |

|

There are several variations on the breakthrough theme:

| The Wedge |

|

| Column Charge |

|

| Frontal Assault, on the oblique |

|

| Strong Side, Right |

|

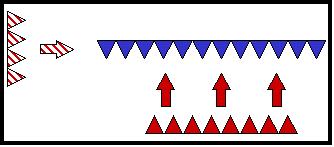

Envelopment

Envelopment involves getting troops into the rear of the opposing

formation or battle line. Sometimes referred to as the first tactical

maneuver, many historians attribute this advance to Philip of Macedon.

Most troops are right-handed. In battle most troops seek to protect their

weapon side (the right) by edging closer to the shield of the man on their

right. This produces a sort of lateral motion in the entire formation with

the result that the entire unit drifts a little to the right. This leaves

the rightmost portion of the formation without any foes to face so they

wrap around the opponent's formation and engage those troops in the rear

ranks. There are two elements to most envelopment maneuvers, the frontal

attack to fix the opponent and the flanking attack to break their line.

There are two types of envelopment, single and double. Each type can be

done in the normal manner or in retrograde.

| Single Envelopment Right, Standard - With the line thinned |

|

| Double Envelopment, Standard |  |

| Single Envelopment Right, Standard - Shifting the line right |

|

| Double Envelopment, Retrograde |

|

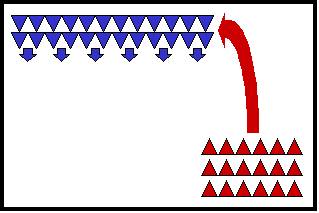

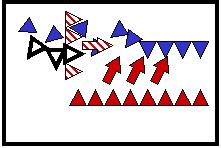

Flanking

The flank attack seeks to use maneuver to increase combat strength.

It does so by allowing your forces to engage the opponent from a direction

other than the frontal arc. The flanking maneuver is rarely used by a single

unit against another single unit (but when it is, it must be executed rapidly

and aggressively and there is some assumption that the defending unit is

somewhat slower or less disciplined than the attacking unit). In the absence

of multiple threats, the defending unit can simply rotate to meet the attack.

This is not to say that the single unit flank is not effective. If the

opponent has placed the bulk of his best Category 1 troops on the front

line and you attack his left flank instead you will prevent many of his

best troops from coming to blows until later in the battle.

| Attacking the right flank |  |

| Attacking the rear-

Properly speaking this is an envelopment since it involves attacking the rear of the opposing formation. I have chosen to include it here because of the similarity to attacking the flank. |

|

In the first example the unit chooses to attack the opponent on

his left flank. In the second, the unit chooses to charge past the

opponent's right flank and then curves back in to attack the opponent in

the rear (envelopment).

| Denying the flank |

|

|

|

| In this example the opponent is attacked by two different units. The first unit, in solid red, fixes the opponent. The second unit, in striped red, attacks the opponent's left flank. In the second illustration we see that the second unit is charging to penetrate the opponent's line and disrupting their formation. Although the second unit has only killed or wounded two of their opponents (and have suffered a casualty of their own in the process) they have thrown their opponent's battle line into disarray. The first unit, still organized, will have the advantage as they move in to support the attack. |  |

Logistics redux

A popular proverb, widely attributed to Napoleon, says: "Amateurs

study tactics, professionals study logistics." This is just as applicable

in the SCA as it is in the real world. A commander with no troops

at the battle is up a smelly creek without a means of propulsion.

A commander with a thousand moderately skilled troops will generally defeat

a commander with 100 outstanding troops. Broadly speaking there are

three times to examine when considering logistics in the SCA: Before the

War, During the War, After the War. All are limited by one very obvious

constraint: this is a game. Every fighter is responsible for equipping

themselves, transporting themselves to the site of the fighting, and maintaining

themselves once they arrive. Even with this constraint in mind, there are

some things that can be done to ensure that armed and trained troops arrive

at the battle site and fight well.

Before the War

Organize your units. Whatever units you are going to form should have at least three months to practice together, against other units. Use all the tools of team-building to forge a strong unit.

Equip your units. Many fighters are sidelined by unserviceable armor. An armorers guild can help ensure that armor is well maintained and broken pieces are replaced. An armorers guild will also help to attract new fighters by making it less intimidating for new fighters to get a basic kit together. Creating tabards and unit banners can involve non-fighters in the unit-building process. Organize a mass rattan purchase and make sure you have weapons enough for each fighter plus one spare for each two men in the unit.

Train your units. Train as you intend to fight.

Make arrangements to transport your unit to the site and house

them. Find everyone with reliable transportation and work out how much

cargo and passengers your unit can collectively carry. Arrange for ride-sharing.

Repeat this process with camping space.

During the War

Make sure you are in the right place at the right time. Find out what the battle schedule is. Coordinate with other commanders to make sure that your unit is where it needs to be when it needs to be there.

Make sure everyone gets fed. A meal plan is an excellent team-building activity and it ensures that everyone gets at least the minimum amount of food they need each day. See the appendix for the excellent article on running a soup kitchen for fighters.

Make sure everyone stays healthy. This is a collection of simple actions that many heavy fighters ignore. Make sure your unit can rest in the shade. If there is no natural shade available, make some with some sort of sunshade. Make sure that people have an opportunity to shower (total body rash is debilitating, uncomfortable, and embarrassing). Make sure that people don't get alcohol poisoning or get into fights. Make sure that there is water and shade on the field.

Make sure everyone is having fun. It is not your job to entertain

everyone, but you can brighten a person's entire event by taking a few

moments to find out how they are doing and pointing them in the right direction.

After the War

Get together and have an After Action Review. Without pointing fingers and regressing into blamestorming highlight all the things you did wrong. Write them down. Highlight all the things you did right. Write them down. Hold a brainstorming session to come up with possible solutions to the things you did wrong. Try them all and adopt the successful ideas. Videotapes and eyewitness accounts are a great help during this process.

Recognize the contributions that people have made. Anyone who has gone out of their way to do something for the unit should be given an 'atta boy'. Anyone who has done something particularly bone-headed should be counseled. Remember, praise in public, criticize in private. It will rarely be necessary to chastise someone for doing something stupid if that action affected the rest of the unit. The guy that leaves the flank un-guarded will feel an awful lot of peer-pressure not to repeat that mistake in the future. Recognition is an important part of team building. That recognition means that the recipient has been recognized, by his peer group, as being not only a "man among men" but an examplar of manhood. Written down in this fashion the concept appears laughable, but it is important on a very deep level.

Fix your gear. A lot of people don't have a lot of funds available

after a war, but this is the best time to fix your gear and improve it

(while the lessons that drove the improvement are still fresh). The possible

alternative is to discover a week before the next war that you can repair

your armor or go to the war, but not both.

Command and Control

This is yet another area where I feel that the SCA closely resembles the Ancient Greeks. What command and control we have is fairly rudimentary. Our leaders lead from the front and our amateur troops have little in the way of training and discipline to condition them to respond to signaling devices more complex than someone shouting. What this means is that a battle tends to consist of a setup where the commander marshals his forces, an initial engagement where the commander commits his troops to the battle according to the plan he has formed (or according to the developing circumstances), and the remainder of the battle where the troops make their own decisions. This situation is horrendous when looked at from one angle, but advantageous when looked at from another. While no commander wants to surrender control of his forces the fact remains that many successful armies throughout history have relied on the initiative of low level leaders. The catch is that in order to take advantage of low level leaders you must develop the leaders and you must institutionalize their leadership. Let me clarify this point. The best low level leaders in the world will not do an army a bit of good if the army is not conditioned to respond to them.

Because of the relatively immense nature of this task (remember:

this is a game) most kingdoms prefer to create command structures at the

upper and middle levels and integrate the existing low level commanders

of various units into the structure. Those kingdoms that do cultivate low

level commanders tend to use them as leaders of ad-hoc units formed in

the heat of battle, as individual exemplars of discipline, skill, and courage,

or as the component pieces of ad-hoc special tasks units.

Command Syntax

Commands are ways of communicating intent. At their most basic every command seeks to convey the message 'this group should go to this place and accomplish this task'. There are many ways of communicating this message to the intended audience. The most simple method is shouting. Further variations on the theme include couriers, drums, horns, flags, mirrors, fires, hand signals, and code phrases. At some point in time most armies standardize their commands to improve performance. This has advantages and disadvantages, particularly in a medievalist milieu. Standard commands ensure that everyone in your force understands what you want them to do. It also means that the forces opposing you do as well. I will first look at a basic command syntax, then I will examine some SCA specific examples, and finally I will propose a template for creating a good system.

I will use the command syntax of the US military as an example because that is the background that I come from. The US military divides commands into two parts, the prepatory command and the command of execution. There is a third part, the supplementary command, which is used to relay commands to subordinate units, but let's come back to that later. The prepatory command alerts the troops to the nature of the action that will be taken. Any American soldier hearing the prepatory command "Forward!" will instinctively prepare to step off and will wait for the command of execution "March!". This command sequence is delivered using a command voice and in a cadence. The command voice is a distinctive sound which originates in the diaphragm, not the throat, and carries through the sound of battle not because it is louder but because it is distinctive, authoritative, and confident. Compare this to the British command voice which is pitched higher than normal speech to carry through the sounds of battle. The cadence of the command, the rythym with which it is delivered, is equally important. A properly delivered command sequence is almost a chant. This rythym helps to cut through the fog of war and allows everyone to anticipate the command of execution.

The SCA does not have a single standard command syntax. Commands vary from Kingdom to Kingdom and Barony to Barony. I think that just about everyone in the SCA understands what the commander means when he yells "Follow me" or "Charge". The typical SCA command would probably be something like: "Utopians, Charge!" It tells a specific group of people what to do and meets the basic requirements of a good command. Unfortunately, it also tells the opponent exactly what is coming. With the exception of Drachenwald and Ealdormeare the SCA tends to be composed of people who speak English. Any command you give is just as comprehensible to your opponents across the way. This makes it difficult to conceal your intent or to achieve any kind of tactical surprise. Many Kingdoms work around this problem by creating 'code word' plays; pre-planned sequences that can be executed when a code word is used. This will be examined in more detail in the section on Standard Operating Procedures.

A good command syntax should be precise but not overly so.

It should follow a standard pattern but should not be so rigid as to limit

tactical flexibility. Above all it should be simple. I think it should

look something like this:

| <Unit Identifier> + [Conditional Modifier] + <Command> + <Prepatory Command> + <Command of Execution> |

The <Unit Identifier> says who the command is intended for. As an additional option, the Unit Identifier can be repeated twice. This helps to get the attention of fighters who are focused on staying alive at the front of a battle line.

The [Conditional Modifier] is an optional command that is used to pass on situation specific information. This information typically modifies how the action to be taken will executed.

The <Command> indicates what action is to be taken.

The <Prepatory Command> literally means "get ready 'cause here we go". I would suggest that the <Prepatory Command> should always be "Ready".

The <Command of Execution> means "do it now". I would

suggest that the command of execution should be "Move".

An example:

Outlands! Charge! Ready! Move!

Or

Utopians! Utopians! At a fast trot! Advance! Ready! Move!

The more experienced among you have already spotted a major flaw in the first example. There is a two beat pause between the command and the actual execution of the command. In the specific case of the command "charge" this is a problem. I won't pretend to offer an easy solution. You can ignore the problem and accept that your opponent will be ready to receive your charge, you can come up with a new command to replace the universal "charge", or you can specify that some commands only use the unit identifier and the command itself becomes the command of execution.

The basic concepts to take away from this section are:

- A command should tell who to go where and what to do once they get there. The when is always assumed to be immediately after the command of execution is given.

- A command should be delivered in a clear and confident voice (from the diaphragm).

- A command should be delivered with a good cadence (think of it as chanting or singing).

It has been pointed out to me that different forms of communication are appropriate for different levels of command. Flags, drums, and horns are generally inappropriate, in the Medievalist setting, for signalling to the troops in general because there is no way for a commander to ensure that all troops know what the signals are and what they mean. They might be appropriate for signalling to sub-commanders because the commander can mandate that his sub-commanders must know the signals. Once the signal reaches the sub-commanders they can relay the command using voice commands. The example given to me involved initiating an attack in echelon where banners were used to inform the army sub-commanders when to begin their advance.

Standard Operating Principles

Standard Operating Principles are the combined concepts that define

the philosophy of fighting for a unit. Throughout this article you have

seen glimpses of the philosophy that I embrace. But there are other philosophies

that are equally valid. It's not a question of better or worse, different

is just different. Principles don't tell you what to do, they tell you

how to do it. Below you will find the text of an article I wrote in 1992,

and updated in 1997, that defines the Standard Operating Principles of

Anglesey as I understand them (13).

| Work as a team,

Everything else we discuss will be subordinate to this principle. We are a mercenary group which fights in melees. While individual fighting skill is to be encouraged and admired, we fight as a group, not a collection of individuals. By cooperating effectively we can overcome opponents who, on an individual basis, are more skilled than us. There are many facets to teamwork. Foremost among these is trust. Each individual must trust everyone else to do their part in an intelligent manner. This allows each person to focus on a single task, confident that they can devote their entire attention to that task and not have to worry about their back. Trust is something that is earned over long periods of association and carries over into aspects other than combat. For example: if you can't be trusted in camp, how can you be trusted on the battlefield? The association that produces trust also allows you to understand people, to know them. Only by talking to people, by being around them can you begin to understand how they think, why they act the way they do. In battle, this familiarity will translate into an increased ability to cooperate. If you know that Bob McBob is an aggressive SOB who believes the best defense is a good offense, and you have fought with him before, then you can have a pretty good idea of how he will react in battle. Know the people you fight with, your enemies as well as your friends. Never fight as an individual so long as one friend remains alive. Work together to get the kills and accomplish the group's mission. No action on the battlefield should be wasted. Use your attack, for example, to create an opening for someone else. You may not kill your opponent, but by moving his shield out of position you make it possible for the spearman two people down to gut him like a fish. In the same vein, watch for the opportunities that your comrades create for you. By working together two mediocre fighters can get as many or more kills than a good fighter who fights as an individual. Every action you take should be intended in some way to help the group. Communicate,

Fight the way you planned,

Don't let the enemy use his resources,

Aggression,

All actions on the battlefield should be carried out as violently and as ruthlessly as safely possible. A melee is not a tournament. We do not greet an enemy, ask him if he's comfortable, and then commence fighting. We sweep down on our foes like a storm. We overwhelm them, knock them down, and never give them a chance to rest or recover. If we can't go through them, then we slash them as we move by or around. When we are gone the wounded survivors should be trying, unsuccessfully, to figure out what just happened to them while we are halfway across the field cutting another unit to pieces. Avoid a fair fight,

Maintain unit cohesion,

Be aware of what's going on around you,

Someone has to be in charge,

Stay mobile,

Sometimes you have to leave your buddies behind,

This also applies to the enemy. Leave the gimps. A man on his knees can still fight and kill. If we gimp five or six of the enemy then we can take them out of the equation simply by rotating our front to focus our attacks on our unwounded foes. A smart foe won't let this happen, but most of them will. Do the math: Ten on ten. We gimp three and rotate our front so that the gimps can't attack us. Ten on seven. Once the entire unit is dead or gimped we can leave all of them where they lay and move on to attack another unit. Don't over focus and let a pocket of gimps cripple our force. Leave them, destroy their buddies who can still walk around, and come back to them later when we can take our time and pick them apart with spears. Take small bites and keep chewing,

Fight on the oblique,

On a larger scale this means not hitting a battleline head-on. Hit them from an angle. In this way all of our forces can engage a portion of their forces. We gain local superiority in numbers, we dictate the terms of the engagement and force the enemy to adjust, and we keep one of our flanks open in case we need to maneuver. Don't do stupid things,

|

These principles work well for Anglesey. Anglesey is a heavy unit

that moves fast and hits hard. It is not a shock unit like the vaunted

Atlantians or a skirmish unit to rival the Outlands or a disciplined legion

like Calontir. These are not the only possible principles, just the ones

that work for my unit. The question here is not "Do you agree with these

principles?", but "What principles is your unit using?" Compare the principles

used by Anglesey to the principles espoused by the Outlands in their War

Book.

| MELEE PRINCIPLES